The Confidence Paradox: Why Self-Assurance Isn't Always Necessary

Written on

Chapter 1: The Surprising Truth About Confidence

In the realm of self-help and psychology, the concept of confidence is often heralded as a crucial component of success. However, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic's book, Confidence: The Surprising Truth About How Much You Need and How to Get It, offers a refreshingly different perspective. Initially, I was skeptical of yet another book promoting the importance of confidence, but a recommendation from one of my favorite authors compelled me to delve into it.

The author, a distinguished psychologist affiliated with the University of London, presents a striking conclusion based on empirical evidence:

“You don’t need confidence!”

This assertion resonated with me, especially since I have always been uncomfortable with the prevailing mantra of “Have confidence!”

To summarize a key argument from the book:

“Just as Coke is not a biologically necessary beverage, confidence is similarly not essential, despite the widespread craving for it.”

This comparison highlights how the pressure to “have confidence!” can create a fleeting sense of well-being akin to the temporary pleasure derived from drinking soda. When discussing the confidence of successful individuals, the author notes:

“Truly exceptional people possess confidence due to their exceptional competence. It’s not high confidence that matters, but rather high competence.”

This point is both insightful and amusing.

Section 1.1: Confidence Versus Competence

The arguments presented in the book are well-supported by research. For instance, a study examining the connection between self-esteem and ability revealed only a modest correlation of 0.30, suggesting that confidence and ability are largely independent of one another.

Further investigation into men who considered themselves attractive showed that only half were deemed handsome by external observers. This pattern extends to intelligence and personality, indicating that many individuals with high confidence may simply be misperceiving their abilities.

A particularly intriguing study from 1995 surveyed 18-year-old students regarding their confidence levels and followed up five years later. The results indicated that those who claimed to be confident were often viewed as deceitful, untrustworthy, and cunning. The author asserts:

“Contrary to popular belief, elevated confidence can have more detrimental effects than low confidence. Not only can an inflated self-image mislead you, but it can also hinder effective communication.”

Subsection 1.1.1: The Advantages of Low Confidence

In contrast, low confidence can be beneficial.

“Low confidence indicates awareness of one’s limitations, which, while uncomfortable, allows individuals to maintain a realistic viewpoint.”

Harnessing low confidence as a catalyst for improvement is vital, rather than letting high confidence cloud judgment. Research shows that individuals with lower confidence levels are more receptive to constructive criticism and tend to develop their skills more rapidly than those with inflated self-views.

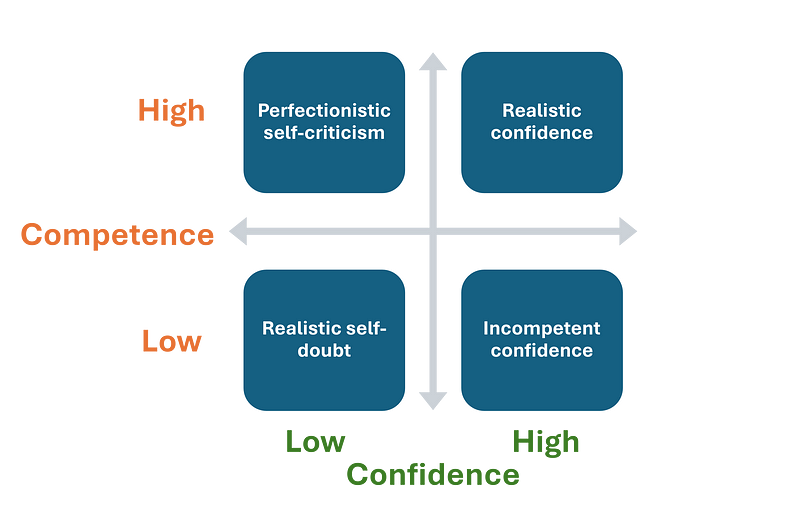

The image above illustrates the “Competence-Confidence Grid,” a concept elaborated upon in the book. While the author discusses strategies for leveraging this grid to enhance abilities, that topic will be explored further in future discussions. For now, the takeaway is clear: “In the end, low confidence can be advantageous, so there’s no need to feel unduly discouraged.”

Chapter 2: Video Insights on Confidence Myths

In the video titled "394: 5 Confidence Myth Busters," various misconceptions about confidence are debunked, revealing the truth behind what it means to be confident.

Jess Weiner’s TEDx talk, "The Confidence Myth," further explores the complexities of confidence, challenging the notion that it is a prerequisite for success.

Psych Times Publication

Helping thousands of everyday people understand themselves and others

psychtimespublication.com

Psychtimes’ Submission Guidelines