Four Scientists Whose Innovations Brought Harm Before Good

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dual Nature of Scientific Progress

Throughout history, scientific and technological advancements have propelled humanity forward in extraordinary ways. Nonetheless, several groundbreaking discoveries have also inflicted significant damage, even as they contributed positively to society.

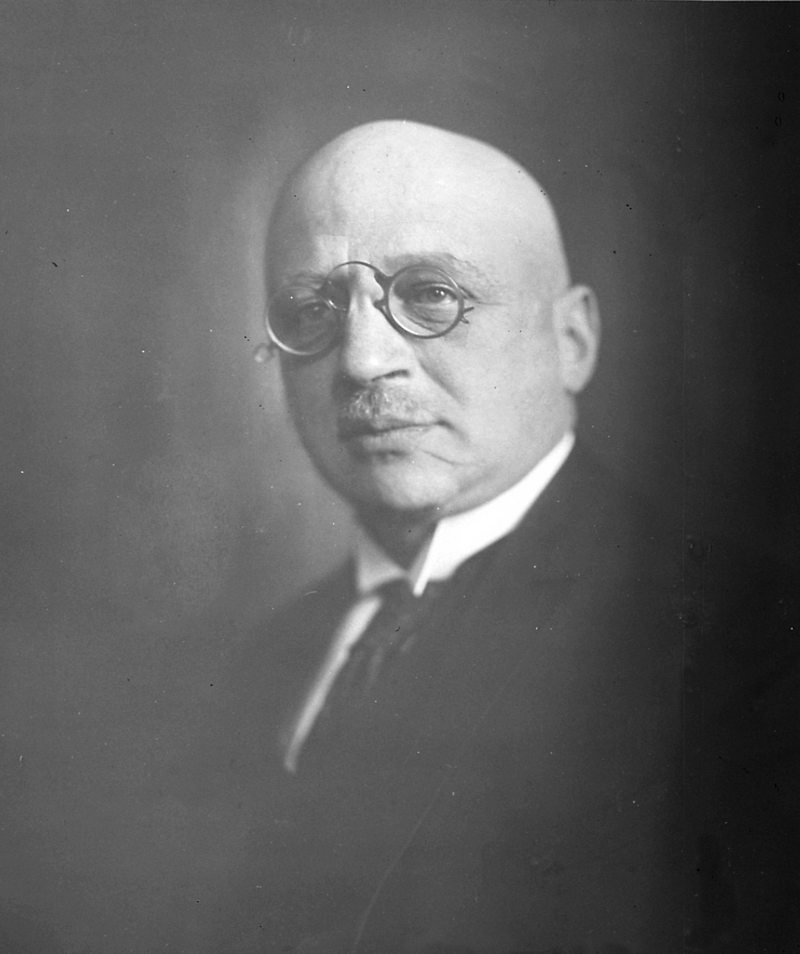

Section 1.1: Fritz Haber - A Complex Legacy

Fritz Haber, a notable German chemist, revolutionized the discipline through his collaboration with Carl Bosch from 1894 to 1911. Together, they developed the Haber-Bosch Process, which enables the direct synthesis of ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen. This innovative process primarily produces potassium and ammonium nitrates, widely used as fertilizers. By making ammonia production more efficient and cost-effective, the Haber-Bosch Process has played a vital role in securing food supplies for a large portion of the global population.

Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his pioneering work, which continues to support approximately 50% of the world's food production today. His contributions have been credited with sustaining two out of every five lives on Earth.

However, the legacy of Haber is marked by a darker narrative. Amid rising anti-Semitism, he converted to Christianity, ostensibly to bolster his academic career. During World War I, he oversaw the development of chlorine gas and other deadly chemicals for trench warfare. Tragically, after his death, the Nazis utilized his research on chemical warfare, employing Zyklon B—a gas derived from his studies—in concentration camps, leading to the deaths of millions, including many of his colleagues.

Section 1.2: Carl Bosch - The Expansion of Synthesis

Carl Bosch continued Haber's work and made significant advancements in extracting hydrogen from various compounds. In 1909, under Bosch's leadership, BASF acquired the rights to Haber's ammonia synthesis method and began constructing the necessary production facilities. By 1913, BASF had initiated the first large-scale ammonia production globally, which escalated during World War I, enabling Germany to produce over 200,000 tonnes of synthetic ammonia annually by 1918 for explosives and fertilizers.

Bosch opposed anti-Semitic policies and advocated for Jewish scientists, but eventually faced immense pressure from the Nazi regime, leading to a strained relationship with Hitler. He resigned from I.G. Farben in 1935 and even contemplated suicide due to the moral conflict of his contributions being used for atrocities.

Chapter 2: The Unintended Consequences of Discovery

The first video "Determined: Life without Free Will with Robert Sapolsky" discusses how our understanding of free will is influenced by biology and societal factors.

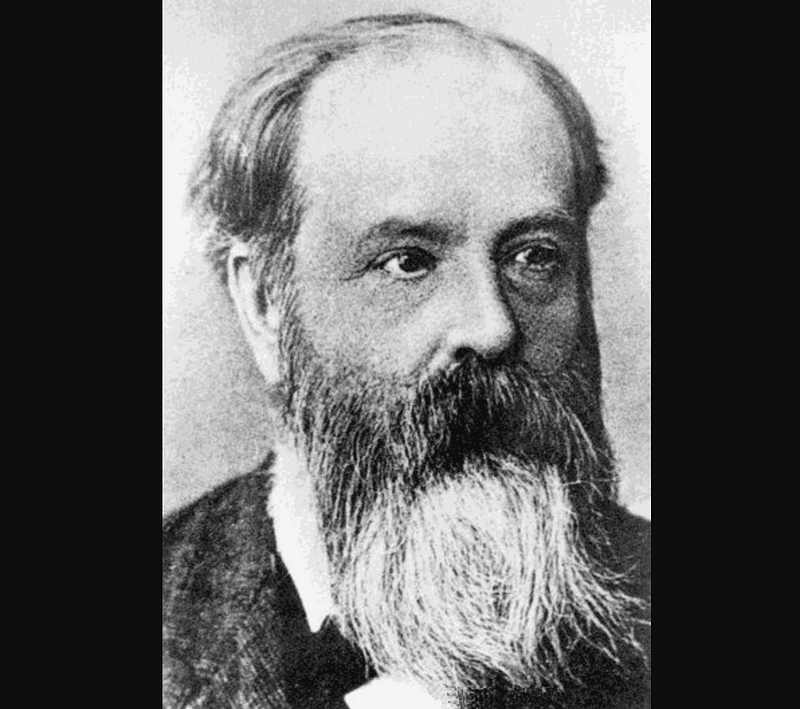

Section 2.1: Frederick Guthrie and Mustard Gas

Frederick Guthrie, a British physicist and chemist, was the first to document the detrimental effects of mustard gas, a chemical weapon he synthesized in 1860. His experiments, which included self-exposure, highlighted the severe health impacts of this chemical agent used extensively in World War I, causing over a million injuries and fatalities.

Despite its devastating effects, the use of mustard gas prompted advancements in cancer treatments during World War II, as researchers leveraged their knowledge of chemical agents to develop effective therapies.

Section 2.2: Ascanio Sobrero and Nitroglycerin

Ascanio Sobrero, born in 1821, is credited with the discovery of nitroglycerin, a compound he deemed too dangerous for practical use. Eventually, Alfred Nobel harnessed its explosive properties to create dynamite. Sobrero's initial reluctance turned to dismay upon learning of the widespread destruction caused by his discovery.

Despite its tumultuous history, nitroglycerin later emerged as a vital medication for cardiac patients, showcasing how scientific discoveries can have unforeseen positive outcomes.

The second video "How Economists Cause Harm (Even as They Aspire to Do Good)" explores the unintended negative consequences of well-intentioned economic policies.

In conclusion, these scientists illustrate the complex interplay between innovation and its consequences—reminding us that sometimes, progress comes at a steep cost.