Superrationality: Decision Theory Clarified through Dilemmas

Written on

Chapter 1: The Flaws in Carl's Reasoning

This discussion builds upon the insights from Chapters I, II, and III.

Carl opts for the two-box strategy in Newcomb's Problem because he assumes that his choice (whether to one-box or two-box) does not influence Omega's prediction. To him, Omega's prediction is already established, and since the past cannot be altered, his decision seems inconsequential.

Carl's Interpretation of Newcomb's Dilemma

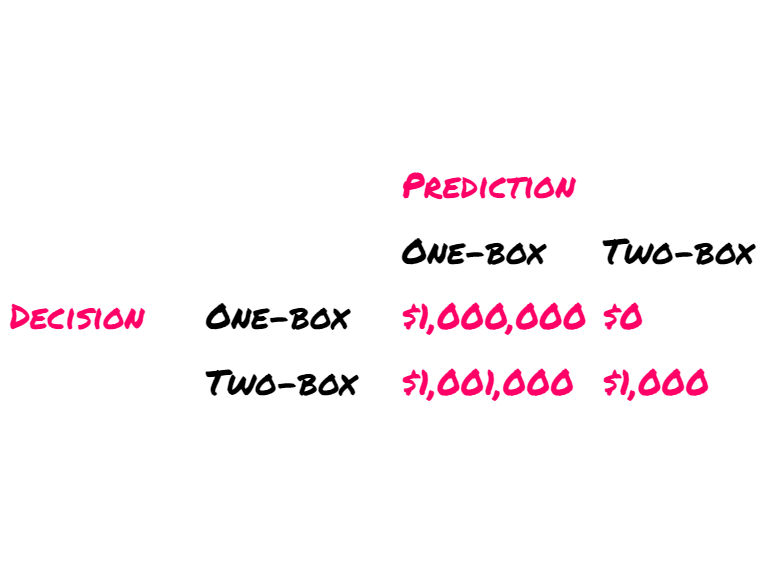

In Carl's view, Omega's prediction remains constant. If Omega forecasts that you will one-box, then opting for two-boxing yields an additional $1,000 compared to one-boxing. Conversely, if Omega predicts that you will two-box, then two-boxing still provides an extra $1,000. Thus, two-boxing appears superior in every scenario. Consequently, Carl adopts the two-boxing strategy, aligning with Causal Decision Theory (CDT).

In contrast to Evidential Decision Theory (EDT), which advocates for actions that signal favorable outcomes, CDT suggests that one should pursue actions that lead to the most favorable results. But what exactly is causality?

A comprehensive explanation of causality exceeds the scope of this series, yet a brief overview is beneficial. Causality pertains to the relationship between cause and effect. Specifically, the effect is contingent upon the cause: if the cause occurs, the effect is more likely to follow than if the cause is absent.

To illustrate, consider a scenario where we observe a large group of individuals. We find that those who frequently sneeze tend to wipe their noses more than those who do not sneeze. However, we also discover that individuals suffering from hay fever wipe their noses more often than those without it. Notably, if we focus solely on sneezers, individuals with hay fever do not exhibit a higher tendency to wipe their noses compared to those without it. The same observation holds true for non-sneezers.

Thus, learning whether someone sneezes does not provide additional insights about their nose-wiping behavior when we already know their hay fever status. However, knowing a person's hay fever status can help us predict if they will wipe their nose based on whether they sneeze.

Causality plays a crucial role here: nose-wiping is independent of hay fever when sneezing is accounted for; hence, hay fever cannot be the cause of nose-wiping—sneezing is the actual cause!

Section 1.1: The Smoking Lesion Scenario

In the context of the Smoking Lesion, the decision to smoke or abstain does not influence the likelihood of developing lung cancer. Here, lung cancer risk is independent of smoking in the presence or absence of the genetic lesion.

In this scenario, the only factor affecting lung cancer risk is the lesion itself, which remains unaffected by one's decision to smoke or not. Therefore, Carl, adhering to CDT, justifies his smoking habit, reasoning that if smoking does not contribute to lung cancer, he might as well indulge in it. However, his two-boxing choice in Newcomb's Problem leads to a loss of $1,000,000 due to Omega's predictions.

Section 1.2: Comparing Newcomb's Problem and Smoking Lesion

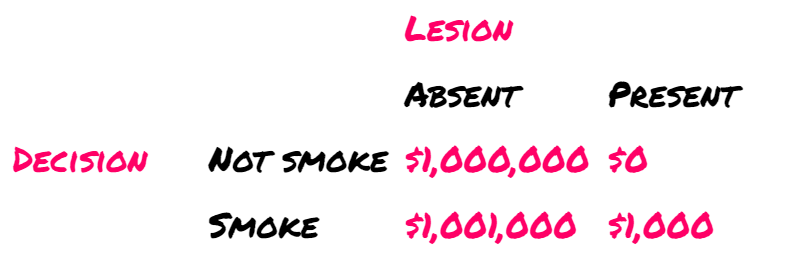

At this point, one might question the distinctions between Newcomb's Problem and the Smoking Lesion scenario. Both dilemmas may seem similar: if we consider the absence of the lesion to be valued at $1,000,000 (due to a reduced lung cancer risk), and smoking to be valued at $1,000, then the Smoking Lesion situation resembles this:

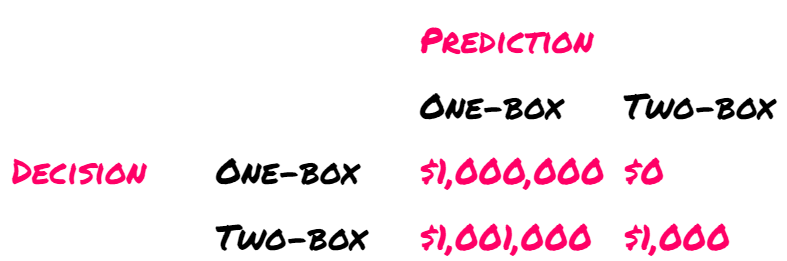

This reflects the same dynamics as Newcomb's Problem, albeit with different labels:

It appears that choosing to smoke in the Smoking Lesion scenario is advantageous, as it consistently yields $1,000 more than abstaining. Similarly, the dominant action in Newcomb's Problem is to two-box.

So why does the author advocate for smoking and one-boxing as the optimal choices? The critical difference lies in Omega's predictive capabilities. To fully grasp this, we will delve into an intriguing thought experiment in Chapter V.

For now, thank you for engaging with this discussion!

If you would like to support Street Science, please consider contributing on Patreon.

The video titled "What Were You Thinking? Decision Theory as Coherence Test - Prof. Itzhak Gilboa" explores how decision theory serves as a framework for analyzing coherence in our choices.