Keeping Schools Open: The Crucial Need for Testing Children

Written on

Chapter 1: The Return to School

As August approaches, millions of children will soon be heading back to classrooms across the nation. We had hoped that extensive school closures were a thing of the past. While there were concerns last year about schools reopening and potentially contributing to community transmission, studies have shown no significant link. Schools that implemented effective masking and ventilation strategies demonstrated a relatively low risk to public health.

This academic year presents new challenges. On a positive note, teachers—who face a higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19 compared to their students—are now able to get vaccinated, and many districts have made vaccination mandatory.

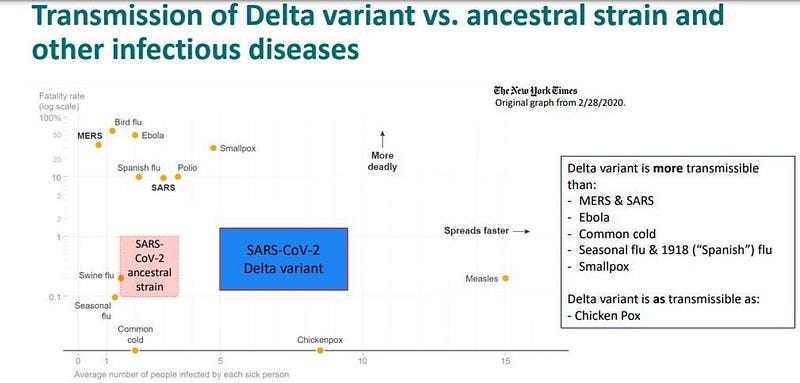

However, the landscape has shifted with the arrival of the delta variant. Research indicates that this variant has a staggering increase in viral loads—some studies suggest up to 1000 times higher than previous strains. An internal document from the CDC even compares the contagiousness of the delta variant to that of chickenpox, estimating an R0 (the average number of people infected by one infected individual) as high as 8.

While schools were deemed safe last year, the question remains: Will they be safe this year? Can good ventilation effectively mitigate the risk when there is so much virus in the air?

Fortunately, children appear to be less severely affected by the delta variant, with outcomes similar to those from earlier strains, meaning the disease tends to be mild among kids. However, since children often live with adults, significant transmission in schools could lead to increased community spread. So, how do we ensure schools remain open?

One frequently discussed solution since the onset of the pandemic is testing. This year, we have access to resources that were unavailable last year. Before the school year began last year, I was in discussions with my local superintendent about implementing a pool testing system for our public schools, but we struggled to find a lab capable of providing timely results.

Now, we have rapid antigen tests, which eliminate the need for laboratory processing. Over 30 rapid antigen tests have received emergency use authorization from the FDA, and many can be administered and interpreted by personnel with minimal training. Additionally, these tests are significantly cheaper than traditional PCR tests.

Section 1.1: The Efficacy of Antigen Testing

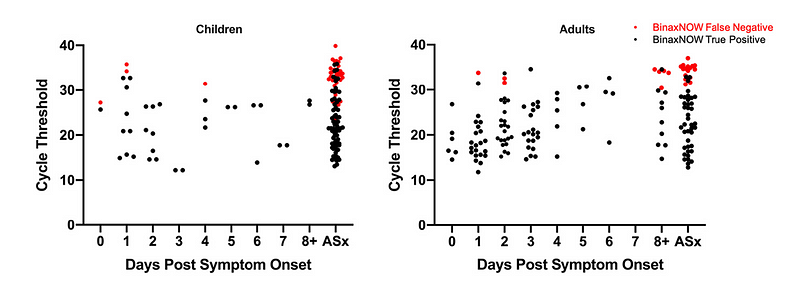

It is widely known that antigen tests may not be as sensitive as PCR tests, but this might actually work to our advantage. A study published in PLOS One involved PCR and antigen tests (specifically, the BINAXNow test, which provides results in just 15 minutes) on 783 children at a testing site in Los Angeles. Of those tested, 226 had positive PCR results—the gold standard. However, only 127 of those, or 56%, also tested positive using the antigen method.

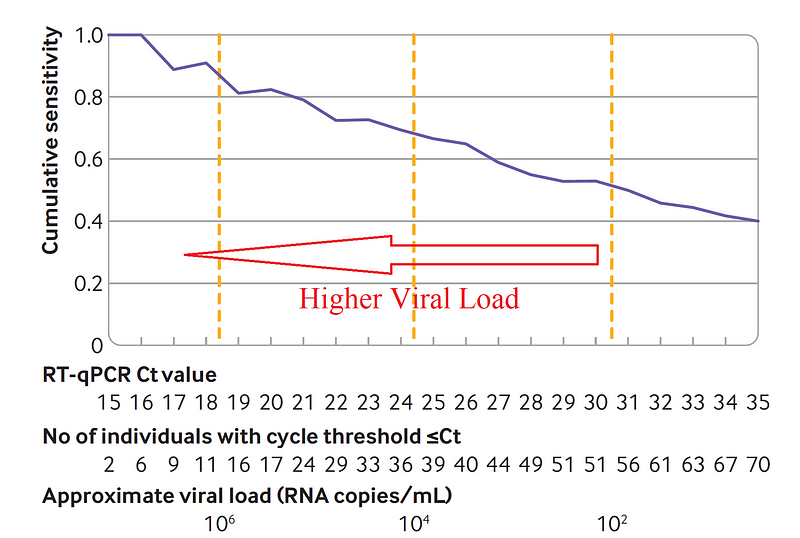

While this might initially seem discouraging, it's important to note that PCR tests aren't simply black and white; they can also indicate viral loads. Lower cycle thresholds in PCR tests suggest a higher presence of the virus. In this study, 16 children had cycle thresholds below 25, indicating they were highly infectious, and the antigen tests identified 15 of them. Importantly, false positives from the antigen tests were quite rare.

Subsection 1.1.1: Additional Studies

A similar study conducted in Boston examined the Binax test in a drive-through clinic with nearly 1,000 children. Among them, 134 were PCR positive, and the antigen test detected 92 of those—approximately 70%. However, in cases with low cycle thresholds and high viral loads, the sensitivity of the antigen test soared to nearly 99%.

Another study from Liverpool, using a different antigen test, yielded similar results: as viral loads increased, so did the sensitivity of the antigen test.

The takeaway is that while antigen tests may not capture every COVID-19 infection, they could effectively detect the most significant cases. Given their low cost and the lack of a need for laboratory processing, could these tests be the key to keeping schools operational this fall?

Chapter 2: Practical Applications of Antigen Testing

Massachusetts has creatively applied this approach. In 582 schools, they implemented pooled PCR testing to identify groups with a positive case, followed by antigen testing to pinpoint the infected individual. They did not provide exact numbers but noted that as long as pool positivity remained low, the costs were manageable, and the strategy could be widely adopted.

The primary factors influencing the costs of antigen screening will be how frequently and how many students are tested. With approximately 56 million schoolchildren in the U.S., screening each child weekly throughout a 40-week school year could cost the federal government around $11 billion, not accounting for potential economies of scale. Excluding vaccinated children (a figure that should increase with the approval of vaccines for younger age groups) would further lower costs. While this represents a substantial investment, considering the financial commitments already made for coronavirus relief, it's a line item worth serious discussion.

Video title: Coronavirus School Disruption: Are Districts Still Responsible for Providing FAPE?

This video discusses the implications of school disruptions due to COVID-19 and the continuing responsibilities of school districts to ensure students receive a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE).